|

AEROBATICS

Hot Links: SILVER PARACHUTE Sales & Service: Official Rigger for the USA Unlimited Aerobatic Team

HOT STICK, The quest for a plaque. Or what itīs like to go from scratch to winning a plaque in the rough and tumble world of aerobatics, by Alton K. Marsh, senior editor at AOPA Pilot magazine. Main photos by Mike Fizer and Michael P. Collins. Cockpit photos taken during training by Carl Austin and Alton K. Marsh.

This article originally appeared in AOPA Pilot magazine, and is reprinted with permission.

Look for an upcoming article about how the photo shoot was put together.

HOT STICK

The quest for a plaque

By Alton K. Marsh

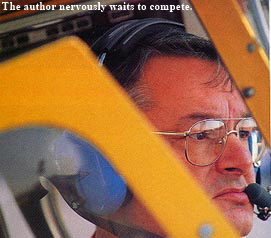

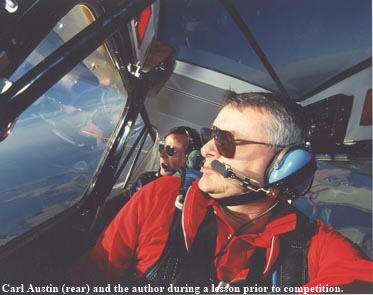

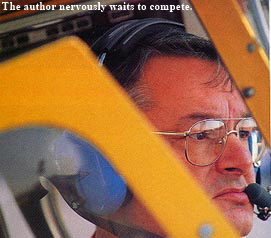

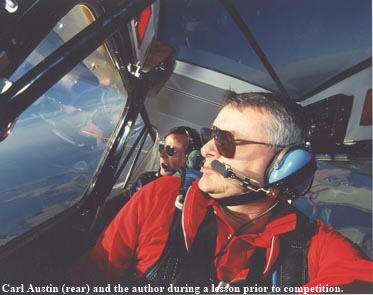

Here I sit, all strapped in, alone and afraid. Actors call it opening night jitters. This is the International Aerobatic club’s Mason-Dixon Clash in Farmville, Virginia, one of the biggest competitions of the year and the first of my aerobatic career. Check the photograph of me waiting for competition to begin; I am definitely afraid. Although aerobatic instructor Carl Austin will ride with me in his 180-horsepower Decathlon to meet insurance requirements, IAC rules do not permit him to help: I am definitely alone. The only thing I have to fear is fear itself, but that’s enough.

Loose change and ballpoint pens have been removed from my pockets so they won’t float around the aircraft during my spin, loop, and slow roll. Those are the maneuvers beginners do, one after the other, three seconds apart: Fly them going one direction, then climb back to 3,500 feet and repeat them going the other way. I have been tightly cinched into Fifty Thirty Pappa by a five-point harness for 15 minutes while contest judges try to cure a problem with their walkie-talkies. For something to do, I retighten the harness and the headset chinstrap. And I ponder yesterday’s lousy practice session.

Hold up an insect. Pretend itīs you. Toss it on its back. See the panic? Thatīs what youīll feel like.

Will I mess up again? The only thing I know for sure is, I want a plaque. To get one, I have to finish in the top three. General Douglas MacArthur once said his last thoughts would be of, “The Corps, and the Corps, and the Corps.” My thoughts are of the plaque, and the plaque, and the plaque. It seemed certain yesterday that I would reach my goal: Only three pilots had registered for the entry-level Basic category by the time I arrived at the Farmville Municipal Airport, and there are three plaques. A guaranteed plaque in return for the $40 entry fee—a good deal. But then the bad news started.

Flash! The number of competitors has jumped to 10, one of the biggest fields of beginners ever. (The pressure builds.) Three of them are flying highly sophisticated Pitts aerobatic aircraft, and I'm in a rented Decathlon. One of them is flying an Avions Mudry CAP 21 air show airplane. (These are beginners?) Aerobatic instructor Eileen Bjorkman, who gave me an hour of training, will compete against me. Three of the pilots have prior experience in competitions, including Bjorkman: I have none. (The stress meter pegs.) The bad news continues. Basic category pilots will fly in the morning, and I am an evening person. My name has been drawn to go first: I hate going first. Oh, yes. And have fun, the contest organizers remind me. Right.

I am wearing a bright red jacket with stripes to put me in the airshow-pilot mood. "Be aggressive," I remind myself. "Attack the maneuvers. Do them as you did in training. Be all you can be." (Or is that slogan taken?) I finally settle on one plan: "Attack!"

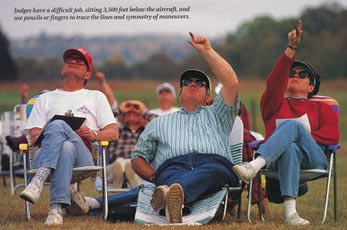

Rudder pedal springs squeaking in a staccato code break my concentration. Has the wind come up? While beginners aren't required to remain in the 3,300 foot-square aerobatic "box" of airspace used for all competitions, they must not cross the "dead line" (in this case the runway) used to protect spectators. Cross it, and the windscreen will fill with tiny judges scattering from their lawn chairs to avoid my dive, instead of the rapidly enlarging cows I normally see. With considerable relief, I realize it is my own feet twitching the pedals, not the wind.

Pilot Managing Editor Mike Collins, photographing my ordeal, asks, "Hey Al, you want a cigarette and a blindfold?" To him, I appear to be awaiting execution. Earlier, I had asked his six-yearold daughter Jennifer what she does when scared. "I close my eyes," she said. Another aerobatic pilot within earshot quipped, "That's just what I do." Fifteen minutes later she was back with a question: "Are you gonna be a scaredycat?"

Finally, the official starter tells me the judges are ready. Over the past six weeks I've had only the 10 hour, beginning aerobatics course taught by Austin, and six additional hours of preparation for the competition. It will have to do. The earliest lessons were cut short by impending air sickness. Each time, Austin's Decathlon proved faster than stomach malaise. I did not hurl. By hour six I had adapted to G forces, no longer feeling tired after each lesson, and the stomach problems were nearly gone—except for the day the snap roll was introduced. I even adapted to inverted flight after a few lessons. Hold up an insect. Pretend it's you. Toss it on its back. See the panic? The confusion? The fear? The flailing little legs? That's what you'll feel like, flying inverted for the first time.

The takeoff today is reasonably smooth; a good omen. I switch to the competition frequency and hear, "Al Marsh is cleared into the box," from Chief Judge Ray Rose; signal panels on the ground go white. Propeller to 2,500 rpm, manifold pressure to 24 inches, trim to 120 miles per hour. Check.

The routine starts with a spin entry. The aircraft must draw a horizontal line as it slows, nose rising to maintain altitude. After the stall, the nose and wingtip must drop (to the left, in this case) together; watch for the halfturn. Now, apply partial right rudder to slow the rotation. One quarter turn more, and full right rudder. Still rotating fast. Wait til the last millisecond, then swiftly move the stick forward to stop on the original heading. Now, dive to draw a vertical “down line,” a decent one this time, but slightly overdone. I go past vertical. Count: one, two, three, and pull. /the pullout from that attitude slams Austin down in the back seat with five Gs of force, more than I normally use in this routine. Since he is further aft, he takes the brunt of it. I am attacking, all right. Other competitors need not worry that Austin will coach me today: When I’m done with him, he’ll be in no condition to say anything. (IAC rules permit beginners to have a safety pilot.)

The loop is coming up in three seconds. During this time I must draw another perfect horizontal line. The aircraft is still trimmed for 120 mph, but due to my greater speed, I must hold forward pressure to avoid climbing. I sight along the bottom of the wing, keeping it level with the horizon. Check the wingtips to make sure the aircraft is level, and pull sharply, enough to load the wings with 3.5 Gs. Swivel the head to the left wingtip, and try to keep the center of the wing on a point on the horizon. A little left rudder, then right. After climbing through the vertical attitude, I increase the back pressure slightly to keep the loop symmetrical as I lose airspeed. Approaching inverted now, I relax the stick pressure to avoid flattening the top. Down the backside, stick pressure increases gradually and left rudder is needed to stay on heading. By the bottom of the loop, I have increased the G load to 3.5 again to maintain the symmetry of the loop.

Going 145 mph out of the loop, I must draw another horizontal line; then it’s time for the slow roll, my worst maneuver. “Slow down. Take your time. Don’t rush.” My mind replays Austin’s instructions of a week ago. Mess up here and it’s no plaque. No pressure, though.

|

Starting the roll is easy: It’s like any other left turn. But that lasts two seconds. Now back to right rudder, still rolling left, to hold the nose up when flying knife-edge on the left side of the fuselage. Approaching inverted, forward stick pressure is blended in to keep the aircraft from turning, and to hold the nose up when upside down; right rudder pressure is continued. So far, so good. Now, into the zone of my discontent—the recovery through right knife-edge to level flight. (I wish I could have slept last night, but I was too excited.) Ease in left rudder to hold the nose up, back off the forward pressure on the stick. My recovery this time is adequate, but not smooth. I mash the left rudder as though killing a bug.Back to Top.

Safely through the first performance, I climb to repeat it in the other direction; once again, I pull five Gs after the spin. The goal six weeks ago was to fly with the fierce control of a Rick Massegee, the aggressiveness of a Patty Wagstaff, the abandon of a Sean D. Tucker, the smoothness of a Bobby Younkin. Now, however, I’ll settle for just getting through this thing. The second loop is accompanied by the stall warning horn, but I make it around. A little altitude is lost in the slow roll, but it is light years ahead of those I did the week before.

The slow roll requires the brain to constantly process ever-changing information about pitch, roll and yaw, and to coordinate the controls through a ballet of constantly movement. I discovered early in my training that my brain has one of the older, slower microprocessors. I need a chip upgrade.

It took 100 practice slow rolls for it to come together. The majority of the practice was done with Austin, but I also flew three times with Craig Brown of Control Aero in Frederick, Maryland, who recalls wearily, “We did a lot of slow rolls.” I confessed my slow roll problem to Patty Wagstaff as she autographed a poster during a convention in New Orleans (more rudder, she said), and sought advice from Rodney Martz of AOPA, Mark Ludtke of Pompano (Florida) Air Center, Pilot columnist Mark Twombly, and John Steuernagle of the AOPA Air Safety Foundation. Then I watched Duane Cole’s video, Flight Around the Axes, over and over.

At times, I even considered whether the slow roll would be easier in a different aircraft. Before training began, I took demo rides in a Pitts S2B with multiple IAC contest winner Bill Finagin of Annapolis, Maryland, and 1992 East Coast Sportsman champion Nancy Lynn, who teaches in an S2B at Bay Bridge Airport in Stevensville, Maryland. Since that time, I have been jealous of Pitts pilots who seem to have power to spare for the maneuvers. You don’t so much take off in a Pitts as you light the fuse. I finally decided, however, the Decathlon is better for the beginner because it slows the maneuvers down, and is less expensive, too.

My last slow roll may not have been perfect, but at least I had a clean routine. Now my fate depends on the other competitors. Leaving the box, I bank sharply and quickly, still performing for the folks below. Austin, perhaps just coming to from my high-G spin recoveries, laughs into the intercom. “Now he turns it on,” he jokes.

The slow roll has been kind to me today, but not as kind to many of the other competitors. I can see my own standing rising until 23-year-old Doug Farley performs in the CAP 21. His slow roll appears to me to be perfect, and his performance threatens to be the winning one until he has trouble with a loop, which ultimately drops him to fourth. When he perfects the loop, future competitors had better watch out.Back to Top.

When all Basic pilots are finished, word is passed that results will take only minutes.

A contest official enters the Farmville hangar to post the standings. Recognizing me as the pest who has peppered him with questions for two days, he calls out, “Al, you got second.” Utter shock. I need to see it for myself before celebrating, and follow him to the wall where the standings are taped. I babble, “I can’t believe it,” over and over until two people begin to stare. Not only will there be a plaque, but it will say “2nd” on it. I can’t believe it. (Oops, there I go again.) There will also be a badge. Today’s competitors scoring a 5 of better on each maneuver will receive a Basic aerobatic badge with stars on top (and a certificate) showing they were judged in an official competition.

First place winner James Howe of Parma, Ohio, who also flew a Decathlon, had previous experience competing in the Basic category. Look for him this year in the more advanced Sportsman category. My score was only 1.3% below his, and I was pleased just to have been close. Third place was won by Russell Sheets of Delaware, Ohio, flying a Pitts S2B. (After the Sportsman category come, in order of increasing difficulty, Intermediate, Advanced, and Unlimited.)

My second-place victory confirmed, I face two choices: Drive home 200 miles without the plaque and let them ship it to me, or wait for a 10 p.m. presentation and arrive home at 1:30 the next morning—a 20-hour day. There is no question that I will wait. I want that plaque in my car prior to departure. It turned out to be a wise decision. It was very encouraging to have Doug Moretz, director of the contest, shout, “Nice job, Al,” during the applause that accompanied my award that evening. I also got to meet a very nice group of people—okay there was a minor food fight and a green bean from one table ended up in the water glass on another. But it was a nice group, all the same.

Even if I never compete again, I still retain the ability to recover to level flight from any attitude.

Would I do it all again? Perhaps, especially if I had adequate practice time. The sportsman category requires 12 maneuvers to be performed in about 2 minutes, and the aircraft must stay in the aerobatic box. Not even experienced pilots get it right every time. It would be easier, of course, if I owned an aerobatic aircraft, had unlimited financial resources (generally $125 to $180 an hour), and knew I had the time for practice as well as contests. But I would have a good shot at getting at least a Sportsman’s badge the first time out.

Alton Marsh and Carl Austin

Even if I never compete again, I still retain the ability to recover to level flight from any attitude, whether it be unusual or positively weird, a useful skill in any aircraft I may fly.

And consider this: Only about 600 pilots compete in IAC aerobatic contests each year, a group more exclusive than the U. S. Marine Corps. And now I am one of them—one of the very proud, the few. Back to Top.

|